The children are connected and online. And now they are connected not just at home, but in school too. With powerful tools, students are ever more able to find out what they want to know, to share that knowledge with people around the world, and to actualize their own ideas. How does the role of the teacher evolve in the connected classroom? Teaching with iPads has challenged me in ways I wasn't expecting and keeps me on my toes because while it's reasonable to expect a 10 year old to teach themselves to use a camera or an app, it is our job to teach them how to do what they are capable of well and responsibly.

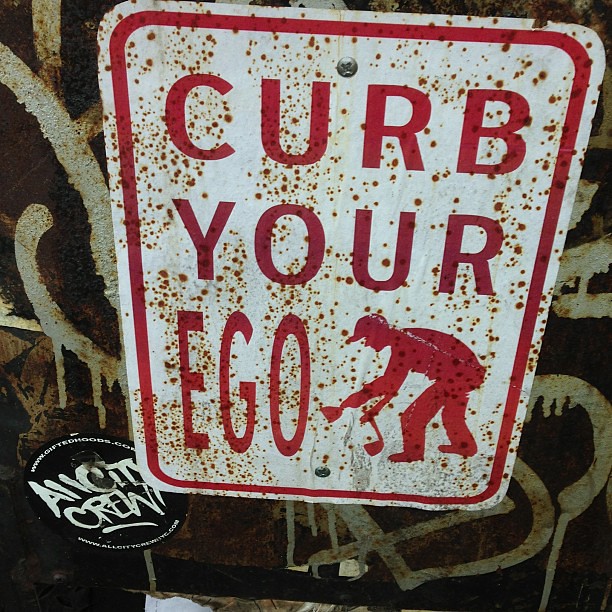

I feel this responsibility most when we are discussing digital citizenship. In the fourth grade we want our kids to be online in ways that are meaningful, but "Safety" and "Privacy" are illusions. We can't promise to protect our students from all of the possible troubles being online brings, as much as we would like to. We

can teach students to proactively use technology in a wise and kind way. We can teach them to decide what kind of mark they want to leave before saving, sending, or posting. We can teach them to be good digital citizen.

Our fourth grade curriculum has a comprehensive, interdisciplinary, digital citizenship program that is co-taught by classroom teachers, our technology coordinator, and our librarian. Good digital citizenship is not just an individual aspiration, it is a community necessity. Ideas and norms are reinforced by all of the other adults and students in the building as we all work with the same lessons and language. Consistency is important in a connected school. The expectations have to be the same for everyone whether they are 4 or 40.

iPad Rollout Training Sessions and "Just In Time" Lessons

Our first sessions with the iPad are designed to introduce the technology (without assuming every child has had the same level of experience with the device) and its power. After exploring the buttons and icons, we talk about what our tech coordinator calls "the most powerful app", the camera. We spend time role playing different scenarios where a photo of someone might need to be taken and how to gain permission from others to take those photos. Children are given the power and language to say no: they don't want to be photographed or they don't approve of an image or they aren't comfortable with how the photographer intends to use it. Our class came up with norms and an agreement that we have posted and will refer to throughout the year.

.JPG)

This exercise made the teachers rethink how we document what is happening in the class (often taking pictures of kids in action without asking their permission). We also developed a contract and those children who don't mind us taking their pictures for our Haiku page or this blog have signed it. Those who are not comfortable did not and we do not feature them in any photos or video.

We are now preparing for training in Google Drive and our school Email system. We will spend some time explaining how to use these accounts for our work flows, but we will also touch on the idea that these are their "professional" accounts to be used for school business. We will review the major points of our school's responsible use policy, and we will practice email etiquette.

Our classroom generally suggests that students not email other students with their Sidwell Friends account unless it is school and work related. We don't have the capacity to truly restrict their access so we do it on an honor system, and last year it worked fairly well. This recommendation is always a debate, but it exists out of respect for different policies about email access among our families and to discourage writing and answering personal emails during the school day. Fourth graders are also still learning to manage offline relationships and need to practice asking for playdates, joking, and apologizing in person.

Our technology coordinator is also developing a series of "just in time" lessons that will be touchstones throughout the year. The topics include integrity, balance, and digital sharing. With this model in place we are prepared to address any new situations that arise. We hope that starting this dialogue in elementary school will impact our students' choices later on and that common language and experiences will enable them to navigate future opportunities with compassion and respect.

Project Redwood Literacy Connection

For the past two years, we have developed an interdisciplinary literature unit using a book called

Operation Redwood by S. Terrell French, a SFS alum.

We have also used

Nim's Island. These books are taught as pieces of literature and we explore the characters, settings, plots, and themes. Sustainability and stewardship connections are made, and students do research about the plight of the California Redwoods. The characters also engage in questionable digital activities, which gives our students a chance to collectively discuss and evaluate such behavior in a meaningful way. With lessons co-developed and taught by our librarian, technology coordinator, and the classroom teachers, students are fully supported as they grow their sense of citizenship in our digital world.